|

A Brief History The USS Kretchmer(DE 329) in World War II

by Dick Sheridan

For the Men of the Kretchmer and their Mates

Lawrence, Kansas

September, 1991

Revised by Art Palmer, Webster City, Iowa, November, 2000

USS Kretchmer (DE 329)

Brooklyn Navy Yard

1945

Richard Sheridan

|

|

Richard served on the Kretchmer from December 1943 until 1945. He was assigned to the Communication division. His duties included standing deck watches, communications duties, including coding and decoding messages, custodian of registered publications.

Richard married Audrey Marion Porter in October 1952. They have one son and one daughter.

After leaving the Kretchmer in 1945, Dick secured his M.S. Degree in Education from the University of Kansas (K.U.) in 1947. He received his Ph.D. degree in Economic History from the University of London in 1951. From 1952 thru 1988, he rose from Assistant to Full Professor at the University of Kansas. He retired in 1988.

Dick and Audrey have visited England and the Caribbean Islands over the years, mostly for historical research and writing.

He claims to be a general handyman around the house, has a computer which he uses as a word processor and in his "old age" has taken an interest in local history and genealogy.

His shipmates thank him for the time and effort he has put into this history of the U.S.S. Kretchmer. They appreciate it very much.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the help of numerous shipmates and mates who encouraged me to persevere in writing the history of the Kretchmer from her commissioning in 1943 until her second and final decommissioning in 1973 and scrapping in 1974. At the beginning I had only a copy of the four-page typescript History of the USS Kretchmer (DE-329) , issued by the Ships' Histories Section, Division of Naval History, Navy Department in Washington, D.C., 1955. With due respect for the author's accuracy, this official history is only a sketch or skeleton of our ship's operations in all three combat areas during World War II and it was written before the Kretchmer was taken out of mothballs in 1956, converted into a radar picket ship for active duty during the Cold War and the Vietnam War. Fortunately, at each of our three Kretchmer reunions in recent years, shipmates have told me of their experiences on ship and shore; and, better still, a fair number have supplied me with valuable materials for which I am deeply indebted. Without these records I could not have written a history about life on board ship and in liberty ports, as well as about our operations as an effective combat unit.

In writing Part 1 on our operations in the Atlantic, Caribbean, and Mediterranean theaters of war, I am much indebted to Henry Asmar for supplying me with the notes he kept as a radioman on the Kretchmer. I also thank Henry Hyde, Soundman First class, for writing to inform me how the Sonar was repaired; to Mike DeChicio and Bill Peralta for permission to quote the long extract from The Mighty "K" , the ship's newspaper; to Ted Webb for writing to tell me of his experiences as a seaman; to Joe Quigley for his account of the torpedoing -- albeit a "tame" torpedo -- of our ship at Key West; to Tom Bullfinch for his vivid account of the hurricane in New York harbor; and to other shipmates who related incidents of our ship's history.

In writing Part 2 on the Pacific War, I am indebted to Tom Bulfinch for making his War Diary available to me. It has been indispensable for making clear our day-to-day operations, the rescue of the prisoners-of-war from Formosa, and the story of the Japanese junk we towed into Okinawa. Henry Samara's "Notes", which were very helpful in writing the Atlantic side of our history, have also been useful for the period from late May to early August of 1945, which included the Kretchmer'S transit of the Panama Canal and our stay in Pearl Harbor. The editors of The Mighty "K" , Mike DeChicio, Bill Peralta, and Eddie Johler gathered together materials that bring out the human interest side of the Kretchmer. I thank them for helping me to write a more personal and anecdotal history rather than one that is dry as dust official history. Useful and interesting letters and enclosures were sent me by Carroll McElrath, James Fishel, Ted Webb, and Dwane Robinson. Fishel sent an attractive booklet which contains many photographs of destroyer Escorts and data pertaining thereto.

As I left the Kretchmer in Manila before it returned to the States via Hong Kong, Singapore, Ceylon, Indian Ocean, Suez Mediterranean, and Atlantic Ocean, I was at a loss how to cope with this most interesting Part 3 of our history. Again I was fortunate, for at our reunion at St. Cloud, Minnesota, Bill Peralta lent me a copy of his "Homeward Bound” diary that he kept on a daily basis. As with the Captain's “War Diary,” it has been indispensable and should provide a stock of anecdotes to keep our reunions going well into the twenty-first century. Charley Manning was also a member of the crew on the long voyage home and his descriptions of the ports of call and other materials in his history of our ship have been of much help in my endeavor.

My good luck in filling gaps in our ship's history actually began at the Emporia Reunion when Allen W. Wilson, a member of the crew on the Kretchmer as a Destroyer Escort Radar, gave me a copy of the booklet describing the Decommissioning Ceremony of the ship and a short history of its operations in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Vietnam theaters of both the "Cold War" and "Hot War" from 1956 to 1973. My thanks to Allan Wilson and also to Dwane Robinson who passed on to me more printed material on the Kretchmer and DER 329 that was sent him by Henry Moll and Ronnie Guertermous, also crew members.

Dick Sheridan, Lawrence, Kansas, 17 September 1991

Further Acknowledgements

I have been very fortunate in the past few years in obtaining some pictures that further emphasize some of the events discussed by Dick Sheridan in the “History of the Kretchmer”.

I took the liberty of inserting them into appropriate places in the “History” and sent a revised copy to Dick Sheridan for his approval. Dick has graciously given me his permission to make this revised version of the “History of the Kretchmer” available to our shipmates.

I was encouraged to include my account of the “banquet” at Hoi How, Hainan Island, on page 52, by several shipmates and first mates after telling about it at our reunion in Jacksonville, Florida.

Dick and Audrey have not been able to attend the recent reunions due to health reasons, but they say that Dwane “Red” Robinson keeps them informed about the reunions.

Thank you Dick for allowing me to be part of this revised “History of the Kretchmer" .

A Brief History of the USS Kretchmer (DE 329)

by Dick Sheridan

Part 1. Destroyer Escorts and Atlantic Warfare

I

Before beginning the history of the Kretchmer, I want to say a few words about the scope, nature, and significance of World War II, of which our ship played a small but important part in several theaters of naval operations.

More than any previous or subsequent war, World War II extended to every continent and sea, "from high in the air to the depths of the oceans and over most of the earth's surface ( Britannica, 1955 , vol. 23, p.. 793Q ." The belligerents included fifty-seven nations, of which the major portion of the cost in military and civilian population and material resources was borne by the United States, British Commonwealth, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, China, and France; and by the three major Axis powers, Germany, Italy, and Japan. The cost of victory for the United States in battle dead was more than 292,100 lives, compared with 56,245 U.S. servicemen killed in the Vietnam War. From 1 July 1940 to 30 June 1945, the federal government spent 323 billion dollars, of which 290 billion went for direct national defense. United States war expenditures rose to thirty-eight percent of the Gross National Product at the peak of World War II, to thirteen percent during the Korean War, and to 9.2 percent during the Vietnam War. Generally speaking, the Vietnam War was the least popular, least understood war in U.S. history; whereas World War II was a flag-waving war with widespread popular support. It was a peoples' war which drew on all of the nation's resources, and in the final outcome it was "United States industrial and military power which provided the additional strength necessary to stem the high tide of initial Axis successes and finally to bring the war to a victorious conclusion ( Britannica , 1955, Vol. 23, p. 793R)."

World War II was the biggest naval war in history. It was waged on a global basis with United States forces committed and engaged in the Atlantic, Caribbean, Mediterranean, and the vast Pacific theaters. In the Atlantic the struggle was chiefly between Allied naval and air forces and German submarine and air forces to secure control of that ocean. It was "a fight for the protection of shipping, supply and troop transport waged by the United States Atlantic Fleet and allied Navies against Axis submarines, supporting aircraft and a few surface ships ( Morison , 1964, p. xii)."

United States strategy was to maintain lines of communication to Great Britain, the Soviet Union, North Africa, and to link the "Arsenal of Democracy," as the United States was called, to beleaguered Britain under Winston Churchill and mount a great amphibious expedition against the European fortress and empire established by Nazi Germany under Adolph Hitler.

Successful antisubmarine warfare required developments in the convoy system, the cooperation of surface vessels and aircraft in the detection and destruction of enemy submarines, and improvements in various devices for accomplishing these goals. Convoys consisted of merchant ships and troop transports that sailed in company, escorted by warships capable of fighting off attacks of enemy submarines, surface vessels, and aircraft. World War I saw heavy Allied losses to German submarines before the convoy system was brought to a high state of efficiency in 1917 and 1918. Enemy submarines were destroyed with the "depth charge," a steel drum filled with high explosives and detonated by a device set to go off at a predetermined depth. Listening devices were improved for detecting the noise of a submarine and therefore its approximate location. World War I also saw the increase use of destroyers for escort purposes, the use of large numbers of small, high-speed antisubmarine vessels, the use of seaplanes and other aircraft for spotting surfaced submarines by air, and the use of radio to facilitate communication between antisubmarine surface vessels and aircraft. ( Outhwaite , 1957, pp. 421-428).

"More than any other phase of the naval war, antisubmarine warfare required a tremendous expenditure of brains, energy, and money in organization, research, new weapons, devices and training methods," writes Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison, the official naval historian of World War II ( Morison , 1956, p.12)." Not only were improvements made in devices found useful in World War I, but also new devices and techniques were developed before and during World War II. Supersonic echo-ranging sound equipment, or Sonar, was invented to enable a trained soundman with a sensitive ear to tell whether the target was a submarine or whale, whether it was stationary or moving, and its approximate direction and speed. The hedgehog was an ahead-throwing rocket weapon used against submarines. Radar acted as the nighttime cat's eyes for antisubmarine vessels and planes, enabling them to detect enemy ships and planes of all types, to be constantly informed of the position of their convoy in darkness and foul weather, to spot icebergs and other surface hazards, and to detect attacks by surfaced submarines. The high-frequency direction-finder (HF/DF, pronounced "Huff-Duff") was a device which enabled antisubmarine vessels to intercept the radio transmissions of surface submarines and spot their location. According to Admiral Morison, "Improved training, new equipment and better administration greatly assisted the Navy to carry out a vigorous offensive against submarines in the latter half of 1943. But it must not be supposed that the enemy had exhausted his bag of tricks ( Morison , 1956, pp. 52-54; 1964, pp. 203-228)."

The destroyer escort program was initiated by President Roosevelt in June, 1940. Congress in the following month appropriated $50,000,000 for "patrol, escort, and miscellaneous craft." Plans were drawn up for the DE by the Bureau of Ships. It is interesting that the first destroyer escorts were built for Britain's Royal Navy which was in dire straits to protect the lifeline to its homeland from increased German submarine attacks following the fall of France in June, 1940. There was a vast expansion and acceleration of naval construction after the Pearl Harbor attack. On 6 February 1942, Public Law No. 440 was enacted. It provided for the construction of 1799 ships and small craft. The building of 250 destroyer escorts was authorized by this law, of which 195 had been delivered to the U.S. Navy by August, 1943. Morison writes that when the DEs finally did come out "they were the merchant convoys' "answer to prayer' and an excellent screen for escort carriers, commanded and officered by the more salty reservists who had served early in the war as junior officers in destroyers and patrol craft and chasers, they justified the wisdom of their designers and planners ( Morison , 1956, pp. 30-36)."

II

The USS Kretchmer (DE 329) was named for Raymond J. Kretchmer, Ensign, USNR, who was killed when the USS ASTORIA 9CA 34) was sunk in action against Japanese Naval Forces on 9 August 1942. Ensign Kretchmer was born at Chicago, Illinois, on 20 January 1917 and attended South Dakota State College. He enlisted at Omaha, Nebraska, on 29 August 1940, and served aboard the USS ARKANSAS (BB 33). He was commissioned an Ensign, USNR, on 12 September 1941 and ordered to the ASTORIA.

The Kretchmer'S keel was laid on 28 June 1943 at the Consolidated Steel Corporation's shipyards at Orange, Texas. She was launched on 31 July with Betty Kretchmer, sister of the ship's namesake, acting as sponsor. On 1 November 1943 the author of this brief history was detached from temporary duty under instruction at the Submarine Chaser Training Center, Miami, Florida, and directed to proceed to Orange, Texas and report to the Superintendent of Shipbuilding at the Consolidated Steel Company's shipyard. Together with a group of petty officers, he traveled from Miami to Orange on a slow train which afforded a fleeting view of a part of the Gulf States in wartime. The greater part of the ship's complement of officers and enlisted men came by train from Norfolk, Virginia to Orange, Texas several weeks after the arrival of the "nucleus crew" from Miami, Florida. ( History of the USS Kretchmer (DE 329 ), Navy Department, Washington, D.C., June 1955, p. 1 (cited hereinafter as Navy Department History of Kretchmer .)

Though slow at first, the rate of construction accelerated and by the early months of 1944 there were seventeen coastal shipyards and a score of inland fabricators that were building and assembling destroyer escorts. According to Commander Edward P. Stafford, USN (Ret.), the shipyard at Orange, Texas worked around the clock seven days a week. He wrote that "while the yard literally put the ship together, the nucleus crew put together the organization that would make her functional when she was complete. But the crew also carried, stowed, tested, calibrated and kept continuous track of what had arrived and what was still required." From the forecastle to the stern, from the engine room to the bridge and masthead, every piece of equipment was tested and supplies checked off or ordered from nearby warehouses. For example, charts and instruments had to be procured for the navigation bridge; guns had to be cleaned and control devices checked; the blowers, pumps, condensers, evaporators, and gauges in the engine rooms had to be tested, checked, and calibrated; anchor chain had to be painted, the windless tested, heaving lines made up, rigged for use, and stowed by the deck gang. Buses transported groups of officers and men to the firing range; and teams of conning officers, sonar men, and helmsmen to the antisubmarine "attack teacher." ( Stafford , 1984, pp 23-33)

The USS Kretchmer (DE 329) was commissioned on 13 December 1943, as Lieutenant Robert C. Wing, USNR, took command. It was a triple commissioning ceremony in company with the USS FINCH (DE 328) and the USS MALORY (DE 791). The Kretchmer'S complement was fifteen officers and 201 enlisted men. It was a long hulled, Fairbanks-Morse diesel propelled destroyer escort, with a maximum speed of 21 knots. Its overall length was 306 feet; extreme beam, 36 feet 7 inches; maximum draft, 12 feet 3 inches; and maximum displacement 1590 tons. Its armament consisted of three 3"/50 caliber guns, one quad 40mm gun, and two twin 40mm anti-aircraft gun mounts. There were four torpedo launchers with torpedoes installed on the Kretchmer when it was built; however, these were later removed and replaced with more anti-aircraft guns.

Six days after commissioning, the Kretchmer sailed down the Sabine River to the Gulf of Mexico and the port of Galveston, Texas. Here the ship went into dry dock where her bottom was cleaned, painted with primer, sprayed with several coats of hot plastic, and equipped with degaussing gear to repel magnetic mines that were placed by enemy submarines and surface vessels in heavily trafficked seaways.

Ted Webb, Seaman First Class, wrote to the author that he had enlisted in the Navy a few days after his thirteenth birthday and he told of some of his experiences aboard the Kretchmer. He recalled the following incident while we were sailing down the narrow channel of the Sabine river. The bridge switched control to me in after steering. Each of the crew had been trained for a special job on the ship; however, during the weeks this training was taking place, I was in the hospital with what the doctors called cat fever. I had zero training up to the time main steering was switched to me. Main steering told me by phone what to do that kept us from running into the river bank. Someone was impressed and must have liked what I did because I was asked to be the main helmsman later while we refueled from tankers at sea.

At sea again on 5 January 1944, the Kretchmer sailed to Bermuda where she reported to the Operations Training command, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, for shakedown training. The author well remembers the night watch he stood as junior officer of the deck on the voyage to Bermuda. Instead of standing the watch on the bridge, he was sent to the after steering room after steering control from the bridge became inoperative. Taking the helm for the first time, he did well to steer the ship within about fifteen to twenty-five degrees of the prescribed course, the propeller leaving a wavy track in the sea.

Bermuda, which is 667 miles southeast from New York, consists of a group of about 300 small islands. Discovered by a Spaniard, the islands were later claimed by Great Britain and colonized in 1612. The beautiful island of Bermuda was the inspiration for Shakespeare's "The Tempest". Bermuda played an important part in supplying foodstuffs to the Jamestown settlement in Virginia and later to the British sugar islands in the Caribbean. After the War of 1812, the British built a large naval base in Bermuda, intending to turn the island into "the Gibraltar of the West." During World War II the United states was given a ninety-nine year lease on naval and air bases in Bermuda. This was part of the Lend-Lease agreement whereby fifty American destroyers that had seen little use since World War I were given to Britain in exchange for the right to build and operate naval and air bases in British possessions extending from Newfoundland to Bermuda, the Bahamas, St. Lucia, Antigua, Trinidad, Guyana, and World War II witnessed the replacement of tourists who had come to Bermuda for rest and recreation by the "tourists in uniform."

All newly commissioned ships make a shakedown cruise for the purpose of training the crew and testing all equipment. Lacking a record of the Kretchmer'S shakedown cruise, it will be instructive to recount briefly some of the experiences of USS ABERCROMBIE (DE 343), as told by Commander Stafford. On the voyage from Galveston to Bermuda, the officers and men engaged in drills and inspections -- "General Quarters, fire, engineering casualties, steering casualties, abandon ship, man overboard . . . and tactical drills with sister ships to form columns or lines of bearing. At Bermuda, the aim of the shakedown training was to provide every ship with "at least a basic ability to perform any task which could conceivably be assigned to her." Upon arrival at Bermuda each ship moored alongside a "mother ship" and staff experts came aboard to check her equipment and provide for essential repairs. The ship then went to sea; the ABERCROMBIE, for example, fired at targets towed on sleds by seagoing tugs, and at target sleeves dragged overhead by low-flying planes. She maneuvered endlessly in tactical and formation exercises with other DEs. . . . She played deadly games of hide-and-seek with a "tame" submarine, learning to search, locate and attack, substituting a prearranged sonar signal for the launching of weapons.

Furthermore, the ABERCROMBIE towed one of the other DEs and was towed in turn, learned to fuel and provision at sea, and underwent almost endless inspections and courses of training and instruction. During the shakedown period of nearly a month, "the raw material of new ship and green crew was forged and hammered into a usable weapon for warfare at sea." ( Navy Department History of Kretchmer , p. 1; Stafford, 1984, pp.41-64)

III

The Kretchmer was pronounced an effective combat unit on 3 February 1944. Shortly afterwards she departed Bermuda for the U.S. Naval Base, Charleston, South Carolina, for post-shakedown repairs and her new duty in the Caribbean region.

The Caribbean or West Indies consist of a chain of islands which stretch from near Florida to the northern coast of South America. Cuba, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, and Hispaniola, which is divided between Haiti and the Dominican Republic, are known as the Greater Antilles; while the many smaller islands and islets of the Lesser Antilles to the east form a semicircle from the American Virgin Islands to Trinidad. First occupied by Amerindian peoples, of whom the Arawaks and Caribs were most numerous, these islanders were unable to cope with the Europeans who conquered their homeland; they quickly succumbed to alien diseases and hard labor in the gold mines until they were nearly extinct. The Spaniards first claimed all the Americas except Brazil and extracted great wealth from the gold and silver mines of Mexico and Peru. Jealous of Spain's great wealth and power, the northern European nations of Holland, England, France, and Denmark outfitted privateering voyages to steal from Spain what Spain had previously stolen from the Aztecs and Incense. Then came the great age of sugar and slavery to satisfy the sweet tooth of Europeans at the expense of Africans who were shipped to the Antilles in chains by the millions to labor on the sugar plantations.

Tourism is today a major industry of the region, although even before World War II the Caribbean islands had attracted to their shores increasing numbers of visitors to enjoy the equable climate, glorious scenery, and colorful folkways and cultures of peoples of chiefly African, Asian and Spanish ancestry.

The Caribbean peoples and their lands were of vital importance to the war effort from 1939 to 1945. From the area came petroleum, bauxite, asphalt, nickel, sugar, coffee, cotton and many other products. Crude and refined oil was carried to U.S. East Coast cities and to Great Britain from Mexico, Venezuela, Curacao, Aruba, and Trinidad. Bauxite, which is the raw material for aluminum which is used in the manufacture of aircraft and other products, came from Jamaica, the British and Dutch Guineas, and Brazil. Cuba, Central America and other territories in the region supplied the United States and Europe with sugar, bananas, coffee, cotton, and tobacco. According to Admiral Morison, "The great industrial cities of the eastern seaboard were dependent on bulk commodities, such as oil, coal, iron, concrete, and lumber. Fuel was necessary for the heat and light of the civilian population during winter in the northern cities, as well as to run their war industries. . . . Only a small part of these heavy commodities could be diverted to the already overburdened railroads." Most vital from the standpoint of military strategy and economic survival in a two-ocean war was the Panama canal and the on-site and outlying naval and air bases which gave it protection. ( Morison , 1964, pp. 252-253)

After post-shakedown repairs at Charleston, the Kretchmer was put under orders from Vice Admiral John H. Hoover, Commander of the Caribbean Sea Frontier, with headquarters at San Juan, Puerto Rico. Hoover was described as "a big man with a long straight nose and a sharp jaw" who was "genial enough" when off duty, but "in the office of the Caribbean Command he was volcanic both as to energy and sulfuric matter ( Pratt , 1944, p. 166)." Taking command of the sea frontier in February, 1942, Hoover proceeded to put it on a wartime footing. He set up three sector bases: one for the sea lanes around the foot of Cuba under Admiral Weyler at Guantanamo; one at Trinidad under Rear Admiral Ollendorf to cover the southern waters of the Caribbean and neighboring South American countries. ( Pratt , 1944, pp. 166-183)

The sea frontier was only beginning to deploy forces of any magnitude when Nazi Germany began to concentrate its efforts in the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico. "May through September of 1942 was the worst period of the war for shipping in these waters," writes Morison, "which in our days of innocence were supposed to be protected from submarine attack by narrow passages, swift currents, and island barriers. Here, in five months, enemy submarines sank an average of one-and-one-half ships per day, and destroyed over one million gross tons of shipping ( Morison , 1964, pp. 257-258)."The U.S. Navy responded to Nazi attacks by ordering a squadron of PBYs to the Caribbean. These were giant seaplanes that flew almost constant missions to search for and destroy surfaced submarines. Furthermore, U.S. shipyards speeded up construction of patrol and escort vessels for antisubmarine warfare in Caribbean waters. For a time these vessels consisted largely of Submarine Chasers, or SCs, "the wooden 110-footers. . . manned by college boys and soda jerkers and plow hands" and equipped with sound gear and depth charges. Somewhat later came Patrol Craft, or PCs, which fundamentally were "SCs grown up to conditions of the ocean and the Second world war ( Morison , 1964, pp. 257-258; Pratt, 1944, pp. 170-183)."

The island of Trinidad lies off the delta of the Orinoco River and is separated from Venezuela by a small body of water. Its population is composed chiefly of black and colored people of African descent and East Indians who were brought around the Cape of Good Hope in the last century to work as contract laborers on the sugar plantations after the slaves of African descent were emancipated. During World War II the island's population was about a half million. Trinidad was a Spanish colony until 1797, when it was conquered by a British expeditionary force and thereafter was a British colony until 1952 when an independent government was established. Trinidad's chief exports during World War II were petroleum and petroleum products, asphalt, sugar, cocoa, coffee, and grapefruit. It was also an important transshipment point for bauxite that was mined in the British and Dutch Guianas. Trinidad is famous for its Carnival, steelbands, and calypso singers who can improvise on any theme with devastating satire. The Gulf of Paria, which is on the west side of Trinidad and is nearly a land-locked sea, is an excellent center for handling the great flow of traffic between the Atlantic and Gulf ports of the United States and the Guianas, Brazil, the River Plate, and Africa, as well as the tanker traffic between the Dutch West Indies and Europe and Africa. Chaguaramas peninsula on the northwest side of the island was the site of the lend-lease naval base with its deep sheltered harbor. ( Morison , 1964, pp. 145-147)

Cuba, the largest of the Caribbean islands, is less than a hundred miles from Key West, Florida, and approximately eleven hundred miles to the northwest of Trinidad. The island contained about three-and-a-half million people during World War II. Discovered by Columbus on his first voyage on 28 October 1492, Cuba was a Spanish colony until the Spanish-American War in 1898, after which it was virtually an American colony until 1959. For more than a century prior to World war II, Cuba was the world's leading producer and exporter of cane sugar. Havana to the north west and Santiago de Cuba on the southeast coast are the largest cities on the island and both possess spacious and deep harbors. Before the revolution led by Fidel Castro in 1959, Havana was called the "Paris of the Caribbean," a tourist center that was infamous for its gambling and prostitution controlled by gangsters from the United States. As a result of the Spanish-American War, the United States acquired naval and air bases at Guantanamo Bay which is about forty miles to the east of Santiago. During World War II the naval base at Guantanamo was commanded by Rear Admiral George Lester Weyler who was born and raised in Emporia, Kansas, the site of the first Kretchmer reunion on 6 and 7 October 1988. Cuba is of strategic importance to the United States, in part because it rests athwart the sea lanes to the United States, Mexico, and the Panama Canal.( Dookhan , 1985, pp. 37-47, 76-77)

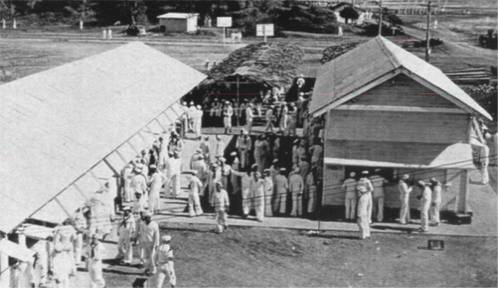

Beer Party at Guantanamo

From Charleston, South Carolina, the Kretchmer sailed to Trinidad to her new duty under the Commander of the Caribbean Sea Frontier. Here she was assigned to Task Unit 04.1.1 to escort merchant and tanker vessels between Trinidad and Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. These were known as GAT-TAG convoys, that is, GAT -- Guantanamo-Aruba, Trinidad -- on the southeasterly run, and TAG -- Trinidad-Aruba-Guantanamo -- on the return voyage. These convoys carried "the bulk trade with South America, and the important tanker traffic originating in the Dutch West Indies." From mid-February to late May of 1944, the Kretchmer, in company with other DEs, escorted five convoys between Trinidad and Guantanamo Bay. For the men of the Kretchmer this was their first sustained convoy duty; it gave them an opportunity to practice their skills in seamanship and antisubmarine warfare but without any encounters with enemy submarines. The author remembers standing deck watches on a "four-on" and "eight-on" schedule, and the rough weather and choppy seas which made him spurn food and drink thrice-boiled coffee to keep awake on the midnight to four a.m. watch. He also recalls the lovely tropical scenery, the colorfully dressed people and their strange languages, the picturesque houses and public buildings. The top tune of the Lucky Strike Hit Parade radio show during our stay in Trinidad was the calypso, "Rum and Coca Cola." The author thought that the verse, "Mother and daughter, working for the Yankee dollar," meant the native women were taking in the sailors' laundry, but he later learned that they earned Yankee dollars by other means. ( Navy Department History of Kretchmer , p. 1; Morison , 1964, pp.262-265)

On 25 April 1944 the Kretchmer was detached from Task Unit 04.1.1 to escort the USS CHIPPEWAS (ATF 69) and the barge it had in tow to Bermuda, arriving on 2 May after a most tedious voyage when day after day it appeared that the ships would never reach their destination.

Two days after arriving at Bermuda a second time, the Kretchmer reported to Commander Task Group 23.3 based at Key West. Here our ship "was designated a school ship to train students at the Fleet Sonar School and to act as a target ship for torpedo aircraft of Fleet Air Wing Five Training Detachment." It was during one of these training cruises that the Kretchmer met with an accident. As the Navy department's history recounts the event, "on May 23rd while she was acting as a target for the torpedo bombers, one of the practice torpedoes broached just before passing under the DE and smashed a hole in the hull. A temporary patch was welded over the rupture and she headed for Charleston and a yard repair availability which lasted from 27 May to 8 June 1944 ( Navy Department History of Kretchmer , p.1)."

Joe Quigley, Seaman First class, was standing watch and saw the torpedo's wake as it approached the ship. He waited until he estimated it would veer off and pass ahead of the ship as normally expected, but when it remained on a collision course he reported the fact to the officer-of-the-deck on the bridge by the head phone he was wearing. By this time, however, it was too late to maneuver the ship to avoid the torpedo. Our damage control party welded a temporary patch over the rupture and the Kretchmer headed for the Navy Yard at Charleston for a permanent patch.

IV

Beginning in June, 1944, and continuing until June, 1945, the Kretchmer was engaged in transatlantic convoy duty. Admiral Morison wrote that the "Battle of the Atlantic" was essentially "a war of maintaining communications with our own forces in Europe and Africa and with our overseas Allies, including Russia; and offensive development of the original policy of hemispheric defense against an Axis approach to the World. "Furthermore", says Morison, "Only Roosevelt and Churchill, of the heads of state concerned in the war, seem to have appreciated the transcendent importance of ocean communications. In all former wars, trade was the primary reason for 'keeping 'em sailing'; and as (Admiral) Mahan proved, that nation won who could both trade and fight ( Morison , 1964, p. xii)."

Curacao, together with Aruba and Bonaire, was a Dutch island colony off the north coast of Venezuela when the Kretchmer arrived there in 1944. It was settled by the Spanish in 1527, and captured from them by the Dutch in 1634. Curacao flourished during the early colonial period as a trans-shipment point for smugglers and a center of the Caribbean slave trade. Its economy revived after a long period of stagnation when the rich oil fields of Venezuela's Lake Maracaibo region were discovered in 1915. The following year the Royal Dutch Shell Company began construction of one of the world's biggest oil refineries in Curacao. Fleets of small tankers brought crude oil from Lake Maracaibo to be refined and shipped in ocean-going tankers to the farthest corners of the earth. A similar development occurred in the neighboring island of Aruba, where, in 1929, a subsidiary of Standard Oil Company of New Jersey built the biggest refinery in the world. Willemstad, the capital of Curacao, is quite picturesque; the hoses are built in the old-fashioned Dutch style with seventeenth-century gables and are mostly painted yellow. The oil boom brought people from a dozen or more nations to Curacao and Aruba, including Spanish, Portuguese, East and West Indians, Caribs, Jews, Venezuelans, Javanese, Americans, Dutch, and Chinese. ( Fodor , 1961, pp. 637-668)

The voyage from Curacao to Naples was especially tedious and uneventful. Admiral Morison wrote that for most sailors and aviators the Oliver Wendell Holmes' dictum "war is an organized bore" had particular application to the Battle of the Atlantic. "It could not be otherwise, when by far the greater part of anti-submarine warfare consisted in searching and waiting for a fight that very rarely took place; yet every escort or patrol ship was supposed to be completely alert from the time she passed the sea buoy until she returned to harbor. Visual lookouts became weary with reporting floating boxes and bottles as periscopes; . . . and the monotonous, never-ending 'ping-ing of the echo-ranging sound gear had the cumulative effect of a jungle tom-tom ( Morison , 1964, p. xvi)."

The records available to the author do not show when the convoy sailed through the Straits of Gibraltar into the Mediterranean Sea. The great rock fortress that forms a well marked promontory was taken from the Spanish by allied British and Dutch forces after a three day's siege on 24 July 1704. During World War II, Gibraltar was a British fortress and crown colony. From Gibraltar the convoy hugged the coast of North Africa to afford some protection against enemy radar surveillance as it proceeded east to Bizerte, Tunisia, and then changed course in a northeasterly direction and anchored in the Gulf of Pozzuoli, in the Bay of Naples on 1 July 1844, after fifteen days at sea. Naples was the second largest city in Italy with a population of 739,349 in 1936. Occupied by German troops, the city was heavily bombed by U.S. and British air squadrons and conquered by Allied forces in October, 1943. ( Britannica , 1955, Vol. 10, pp. 334-337; Vol. 16, pp. 78-81)

The Kretchmer was back at sea two days after anchoring in the Gulf of Pozzuoli with her section of tankers and was later joined by tankers from other ports enroute to the United States. Arriving at Norfolk, Virginia on 16 July, our ship began a twelve-day shipyard availability. Then between 12 August and 1 September 1944 another transatlantic convoy run was made to Naples and back to the United States. ( Navy Department History of Kretchmer , p. 2.)

The author is indebted to Henry C. Asmar, Radioman Third Class on the Kretchmer, for giving him copies of notes he kept while on the ship. His notes begin during our short stay at Naples on 1 and 2 July 1944, when "the crew sold cigarettes etc. to the natives not realizing how low supplies were getting." The ship got underway about 0800 on Monday, 3 July and enjoyed good to fair weather and calm to choppy seas for several days, maintaining a speed of fifteen knots. The Rock of Gibraltar was passed on the 6th, at which time Asmar wrote, "We are running low on food supplies." The next day the ship's store ran out of cigarettes. The men smoked each cigarette until it burned their fingers and then began to roll their own. On the 12th he noted, "No cigarettes, tobacco, or soap and a limited food supply. We all learned a lesson this trip. Heaven help the ship's store 'in Norfolk' when this crew lands tomorrow." Arriving at the Norfolk Navy Yard on the 16th, the men rushed to the ship's store so fast that had there been "an official timekeeper on hand this would have been when the four minute mile (record) was broken."

After a gap in his notes during shipboard availability at Norfolk, Asmar wrote that the Kretchmer got underway at 0630 on 28 July 1944 with a task force which consisted of twenty-seven other ships. There were two aircraft carriers, HMS PUNCH and USS SHAMROCK BAY; three destroyers (DDs); five DEs; one CL; five troop ships; six tankers, and five merchant ships. On 31 July he wrote that the weather was great and the sea calm. "We passed Bermuda today. We received reports that there are enemy subs about 150 miles south of us. At 2200 our position 30 degrees 20' lat., 54 degrees 05' long., course 95 degrees E., speed 15 knots." On 1 August our radiomen picked up a U-boat signal bearing 105 degrees East. A destroyer was sent to investigate but no contact was made. Another signal from a U-boat was picked up on 3 August, but we could not get a definite bearing. The Rock of Gibraltar was passed late on the night of 8 August. Algiers was passed while cruising along the coast of Africa on 10 August. "Genera quarters was sounded at 0700 and again at 2330. At 2400 our course was 85 degrees E. Speed 15 knots.ship's roll 1 to 2 degrees. "The Kretchmer and the ships it was escorting anchored in the Gulf of Pozzuoli on Saturday, 12 August and remained there until Friday, 18 August.

Aircraft Carrier in the Mediterranian

The ten-day layover at Naples gave all of the men of the Kretchmer liberty and shore leave to see Naples and neighboring cities and points of interest. Naples presented a scene of extreme poverty and desolation, large sections of the harbor and city having been destroyed by British and U.S. air raids. The German army was said to have taken precious art objects and other valuables when they retreated north after occupying the city. Crew members saw these sights, especially the slums of Naples. They also visited the scenic Isle of Capri, Sorrento, Vesuvius, and the ruins of Pompeii. The author attended a performance of Giusseppe Verdi's opera, "La Traviata," at the San Carlos Opera House and joined a group which hitched a ride up the Appian Way to Rome, where in a borrowed jeep, they made a whirlwind tour of the ancient city, visiting the Vatican, Forum, Colosseum, Hadrian's Tomb, the Catacombs where early Christians hid from their oppressors, and other famous sites.

Refueling from a Tanker in the Mediterranean

Asmar noted on Friday, August 18, 1944,"We got underway at about 1530 heading back to the United States with our convoy. There are troop ships carrying about 15,000 men. They have been here over two years and are going home." Three days later he wrote, "We passed the Rock of Gibraltar to-night. We are now in the Atlantic. Course 275 degrees W.Speed 14 knots. Ship's roll about 5 deg." On the 26th a U-boat was sighted 175 miles away, and the following day the convoy went off course for about twelve hours to avoid running into the reported U-boat. Bad weather was reported on the 30th: "We got tossed around for a while. Ship's roll was about 25 deg. The sea calmed down this afternoon." The following day when the weather and sea left nothing to be desired, the Kretchmer left the convoy with a tanker and escorted it to Norfolk, Virginia, arriving there at about 2145, then "leaving the tanker and headed back to New York. Course 25 degrees NE. Speed 20 knots. Ship's roll about 1 deg." On Friday, 1 September 1944, the Kretchmer arrived at Brooklyn Navy Yard for a three-weeks stay to undergo maintenance and repairs.

V

To Lieutenant Thomas Bulfinch, Executive Officer of the Kretchmer before he succeeded Lieutenant Robert C. Wing as commanding officer, the single most memorable event in the ship's history was the struggle to save the ship in the raging hurricane in New York Harbor on 14 September 1944. The New York Times reported an Atlantic hurricane moving northwest from Puerto Rico on 11 September. Two days later the Atlantic Seaboard from Cape Hatteras to Block Island was said to have been hit. On the 14th the hurricane was said to be the worst storm since 1938. Wind velocity attained a record of 109 miles per hour at Hartford, Connecticut; cottages along the shores of Long Island were devastated; New York City reported 13 dead and 27 injured, many communities were without light and power; a destroyer and two coast Guard patrol boats were sunk. After the hurricane passed on, New York city employed some 5,000 men to clear the debris.

On 13 September 1944, the Kretchmer was in the Brooklyn Navy Yard when orders were received to rendezvous with a friendly submarine and conduct training exercises off Montauk Point, Long Island, on the following morning at 0700. After getting underway, the officers and men on the bridge observed the barometer to be falling rapidly and the seas becoming more turbulent as the wind velocity increased. Although the ship had not been warned, captain Wing sensed that we were in a perilous situation and turned back to New York harbor. The full force of the hurricane struck the Kretchmer as we went through the submarine nets into the outer harbor about 1700 on the 14th.

For the next six hours the officers and enlisted men waged a battle to save the ship from grounding, collision with other craft, or crashing into docks and other fixed objects. Attempts to get the ship up to a dock failed in the face of near-blinding rain, Engineering Officer Jim Bryson reported to the bridge that very little compressed air remained to start and stop the engines. Fortunately, by this time the wind had abated somewhat and it became possible to pull alongside a dock in South Brooklyn and secure the ship. Some of the men even went on liberty after the ordeal. Captain Bulfinch told this story at the first reunion of the Kretchmer at Emporia in October, 1988. To him the teamwork and coordination manifested by all members of the crew was a magnificent achievement and augured well for our future duty in the war zones of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

After maintenance and repairs, our DE was made up part of Task Group 21.9 with orders to escort merchant convoys between New York City and the Solent, Portsmouth Bay, Portsmouth, England. The convoy to Portsmouth sailed between 20 September and 16 October 1944, and the return convoy between 7 November and 3 December 1944, both without encountering enemy submarines. ( Navy Department History of Kretchmer , p. 2)

Convoy from Portsmouth, November 1944

On Sunday, 3 December 1944 the Kretchmer and other vessels in the convoy arrived at New York after a ten-day voyage from Portsmouth, England. On Saturday, 16 December, our DE shoved off for New London, Connecticut. There followed two days of gunnery practice, shooting at a sleeve towed by a plane, and practicing hedgehog runs on a "tame" submarine. At about 1300 on Thursday, the 21st, we headed back to New York, arriving at the 36th street pier at about 1400 on the 22nd.

On Monday, Christmas Day, 1944, the Kretchmer shoved off about 1300 from the 36th street pier and anchored out in New York harbor to wait for the convoy to form. The following morning we got underway with a convoy consisting of oil tankers, cargo ships containing planes and ammunition, and troop transports carrying about 55,000 soldiers. On our fifth day out we ran into a severe storm; our ship and men took a beating as we pitched and rolled 40 to 45 degrees. Convoy speed was reduced from fourteen to ten knots. On New Year's Day, 1945, we dropped back of the convoy to escort a tanker that had fallen behind during the night. "This ship and crew are taking a pretty bad beating," Asmar noted. "The mighty "K" is a tough ship, no signs of any damage, and the crew is just as tough," he added. By 3 January the weather and sea had moderated and we were well out of the storm.

The radio shack was kept busy on Thursday, 4 January. "Messages for us have been coming in with hardly a few minutes rest in between," said Asmar."We have word that the convoy may be being followed by a wolfpack of German subs. No sonar contact made. At 2200 our position is about 48 degrees 20' N., 17 degrees 07' W. course 085 E., speed 15 knots, ship's roll 10 to 13 deg." The following day when Asmar learned that our destination was England, the weather continued poor and the sea a bit choppy, but clear and the water is almost like a sea of glass." At about 2100 a submarine contact was made and general quarters sounded. "We fired a pattern of hedge-hogs in the area of the sonar reading. The hedge-hogs exploded but there was no official verification of a sub being hit. We were on alert for the rest of the night." On Sunday, 7 January, we left the convoy and proceeded to Cardiff, Wales and dropped anchor outside the harbor. We remained there overnight and the next morning passed through the locks into the harbor. Cardiff is the principal city in Wales and from about 1850 to 1914 was the greatest coal exporting port in the world.

After two days at Cardiff, the Kretchmer got underway and sailed in a westerly direction to Milford Haven, Wales. On 10 January a radio dispatch informed us that two British ships had been sunk by German U-boats, one in our area and the other off the coast of Gibraltar. The following day we had three general quarters and most of the crew slept with their clothes on in anticipation of a submarine attack which never came. Shoving off from Milford Haven on the 11th, our convoy consisted of about twenty ships and five DEs.

Our sound gear went dead at about 0200 on the 13th. Henry Hyde, Soundman First Class, explained in a letter that the failure was diagnosed as a short in the power transformer. Not having a spare transformer aboard, Hyde decided there was nothing to lose by attempting to dismantle and repair the transformer, even though in school he had been told that this could not be done. After unwinding the wire to the point of the short he found that the paper-like insulation was destroyed. Lacking such insulation, Hyde suggested the friction tape be used. But friction tape was too thick, and at the suggestion of Walter Artus, SoM 3/c, scotch tape was used instead. After several tedious hours the wire was rewound but was still too thick. Hyde then put the core in a vise and squeezed it until the laminations would go on. With bated breath, he put power to the transformer and no smoke issued forth. The transformer was reinstalled and performed satisfactorily all the way back to New York where it was replaced. To rephrase the verse of an old rhyme, "Had we not had ingenious soundmen and scotch tape, the Kretchmer might have been lost."

Since the weather affects seamen and ships they sail in many ways, they need to know the wind velocity and whether it is rising or falling, whether the barometer is rising or falling, whether there will be clear fine weather or fog, clouds, rain or snow. For several days out of Milford Haven we enjoyed excellent weather with beautiful sunny days, some choppy seas with swells, but on the whole fairly smooth sailing. Then on Thursday, the 18th, when we had just passed Bermuda on a course of 270 degrees, the weather turned bad with very big swells, spray going over the flying bridge, and, on the 19th, the greatest ship's roll up to that time of 53 degrees. Good weather and calm seas returned on Saturday, the 20th, when we departed from the convoy to escort a cargo ship to Boston, while the rest of the convoy proceeded to New York. After leaving the ship at Boston, we returned by way of Cape Cod and Long Island Sound and docked at 36th street pier, Brooklyn, on 21 January at about 1500.

At 0945 on Friday, 2 February 1945, we departed New York harbor and docked at Sandy Hook six hours later to take on ammunition. From there we sailed to Casco Bay, Maine. On the 6th, according to Asmar, "we made practice runs on one of our subs. We used hedge-hogs most of the day, and late afternoon we shifted to practice depth charges. We would drop a smoke bomb when the sub was located. The USS TRIPPE, a destroyer, picked up a sub that gave the right recognition signal but was unable to give any further information. All ships in the group were ordered to locate and destroy that sub. We hunted all night but no contact made. The search for the submarine continued until about 2200 of the following day when the Kretchmer departed and headed for New York, arriving there about 1100 on the 9th.

Our next duty was to escort a convoy to Greenock, Scotland by sailing around the north of Ireland to avoid enemy submarines in the English Channel. Special sea details were set at 2400 on 10 February 1945, and we anchored out in the harbor waiting for the convoy to form. Getting underway about 1200 on the 11th, we learned that the convoy consisted of twenty-seven ships and six escorts. On this voyage we took on a new passenger, a dog that the crew named "Boats". Boats seemed to be getting his sea legs the first few days, but on the 15th, when the sea turned a bit choppy with some pretty big swells, Boats was washed overboard by a wave coming over the fantail. It was almost miraculous that as he was going under the life line, another wave washed him back on board and Boats thus barely escaped that grave of seamen and their dogs, "Davy Jones locker." The weather became more severe the day following the dog episode when the destroyer escort USS DAVIS, one of the escorts in our convoy, had a man washed overboard and it was most tragic that the search for him eventually had to be abandoned. On the Kretchmer we had trouble with the evaporators that converted sea water into fresh water, which Lieutenant Jim Bryson and his men proceeded to repair. For several days the weather and sea were bad, at the same time that there was only enough fresh water for cooking and drinking. Salt water showers left a less-than-clean feeling, adding to the misery of the constant rolling and pitching of the ship.

We arrived at Greenock on the Clyde River on 22 February 1945, with liberty for the port section until 2330. The Clyde, the third largest river in Scotland, is one of the most important rivers in the world on its lower course for its seaborne commerce and industries. Greenock is on the south shore of the Firth of Clyde, and twenty miles from Glasgow, the largest city in Scotland with a population of a million people in 1951. Greenock, which is the birthplace of James Watt who invented the steam engine, was important in World War II for its shipbuilding, engineering, sugar refining, worsted and woolen manufacturing and production of aluminum products. ( Britannica , 1955, vol. 10, pp. 861-862)

The stay at Greenock was enjoyable for the men in our liberty parties. They met up with pretty Scots lassies and had little competition from Scots lads who were mostly away doing military service on ships and shore stations scattered around the globe in what was then the British Empire.

Departing Greenock on 27 February escorting one tanker, we joined the main convoy the following day. While underway two of the escorts that joined our convoy made what were believed to be submarine contacts and dropped depth charges with unknown results. On 3 March our sonarman reported a contact believed to be an enemy submarine. We made a run on the target, firing a pattern of hedge-hogs. After making a few dry runs the contact was classified as "non-sub". Other than these contacts the voyage back to the States was uneventful except for some bad patches of weather and high seas.

We arrived at New York at about 1300 on Friday, 9 March 1945. After unloading ammunition, the leave party left on a nine-day leave. The Kretchmer was in Brooklyn Navy Yard for repairs from the 10th to the 19th. We got underway for Casco Bay, Maine the following day. Asmar reported very cold weather for the first day of spring on the 21st. The next day we had gunnery practice. "We were firing at a remote controlled plane. There were two other ships shooting with us. The Mighty "K" was the only one to shoot down a plane." For several days our gunnery crew practiced night firing and the antisubmarine warfare team practiced tracking a "tame" submarine. About 2200 on the 29th we set a course for New York, arriving there on the morning of the 30th.

In New York we learned that what turned out to be our last voyage across the Atlantic under combat conditions was for the purpose of escorting some merchant ships to Southampton, England and back. We got underway at 0945 on Saturday, 31 March 1945, on a foggy morning with such poor visibility that we dropped anchor and waited for the fog to lift. "When the fog broke a bit, the convoy formed and we were underway. There were 32 ships in this convoy. Two are troop-ships. Also six escorts . . . . Speed 14 knots. The sea swells are big. We are being hit on the port side by some pretty big waves. At 2200 our position 41 degrees 21' N., 36 degrees 39' W. speed about 12 knots. Ship's roll 35 to 40 deg."

By the 8th the sea had calmed down slightly; however, we were still being tossed around quite a bit. On the 11th, when we had just entered the English Channel, the sea was calm, our speed was 14 knots, and the ship's roll about 10 degrees. We escorted part of the convoy to LeHavre, France the following day and arrived at Southampton, England about 2000 and tied up to the dock on the 12th. During the two-and-a-half days in port, some of the men took a train the short distance to London and saw the devastation caused by the Blitz of 1940 and the Buzz Bombs then coming across the channel from German launching pads on the continent. The author remembers climbing to the tower of St. Paul's Cathedral and seeing the bombed-out area of East London.

Getting underway at 1600 on 11 April, we anchored out in the harbor near Portsmouth to wait for the convoy to form. At 2200 the same day we got underway with six troop ships and several DEs as escorts. The first part of the voyage went smoothly except for a change of course to avoid and U-boats that might be in the area.

But on the 19th trouble began when a worn out steel cable was thrown overboard from the Kretchmer and got tangled on the portside shaft and propeller. Some of the crew dove down and tried to free it but without success. We were then detached from the convoy and ordered to the Azores where we hoped to have the cable removed. The Azores were island colonies of Portugal and neutral territory during World War II and no one was allowed off our ship. Arriving there on the 22nd, the cable was removed without damage to the shaft or screw. By speeding at twenty knots, we hoped to catch the convoy before it reached New York.

Writing on 24 April, Asmar said, "The U-boat that we feared might be in the area struck today, a short distance north of us. The U-boat torpedoed and sank a DE (USS DAVIS). There were sixty-six survivors. Eleven DEs made a sweep of the area about 300 yards apart, with a hedge-hog attack on the U-boat at about 1835. The U-boat was damaged and forced to surface. It was then sunk at exactly 1444. The sub was the U-boat 546; the captain's name was Just. There were about thirty survivors."

Pt 2

|